The Florida Board of Education on Wednesday approved new standards for the teaching of African American history in Florida schools, as well as other social sciences, that reflect what critics describe as a “whitewashing” of Black history.

The 216-page document detailing new academic guidelines for K-12 schools was approved at a board meeting in Orlando, but not before facing criticism by numerous educators, Democratic politicians, as well as the Florida Education Association (the statewide teachers union) and the NAACP.

Critics argued the new standards “omit or rewrite key historical facts about the Black experience” and ignore state law about required instruction.

Already, the changes have garnered national attention — largely due to a section of the middle-school standards that would require instruction on “how slaves developed skills which, in some instances, could be applied for their personal benefit.”

Vice President Kamala Harris, who paid a visit to Florida this week, condemned the language. At a conference for the Black sorority Delta Sigma Theta in Jacksonville on Thursday, Harris shared, “Just yesterday in the state of Florida, they decided middle school students will be taught that enslaved people benefited from slavery!”

Kamala Harris: “In the state of Florida, they decided middle school students will be taught that enslaved people benefited from slavery!”

— The Post Millennial (@TPostMillennial) July 20, 2023

Moreover, new standards for high school instruction would expose students to another hotly debated message: To meet the new benchmarks, lessons on white supremacist-led massacres against Black Americans — including, but not limited to the Rosewood massacre in 1923 and Ocoee massacre of 1920 — will include instruction on violence both “against and by African Americans.”

Members of the board, however, as well as the state Department of Education, defended the new standards. MaryLynn Magar, a DeSantis-appointed member of the education board, said on Wednesday that “everything is there” in the new history standards and “the darkest parts of our history are addressed,” the Tallahassee Democrat reported.

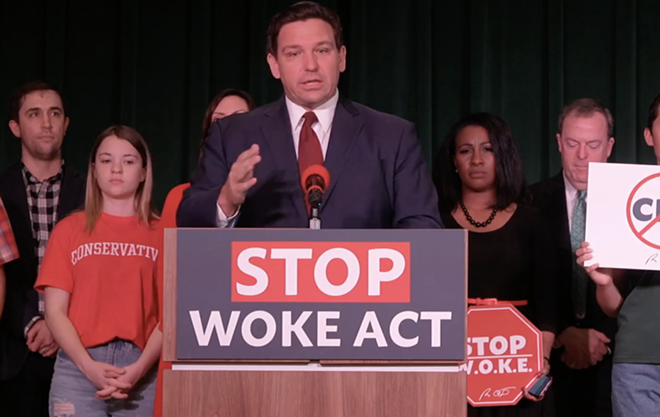

Manny Diaz Jr., the state’s education commissioner (and a former Republican lawmaker who sponsored HB 7, also known as the “Stop WOKE Act” of 2022) also defended the changes.

“This is an in-depth, deep dive into African American history, which is clearly American history as Governor DeSantis has said, and what Florida has done is expand it,” said Diaz.

In fact, the new standards were adopted as a curriculum update made necessary by HB 7, dubbed by Gov. DeSantis as the “Stop Wrongs To Our Kids and Employees Act,” or “Stop WOKE Act.” Separate rules were also adopted Wednesday concerning preferred pronouns and bathroom use by transgender students and educators in schools.

House Bill 7, approved by the GOP-dominated legislature in 2022, bans instruction that characterizes one race or gender as morally superior to another, and bars educators from teaching anything that could make students feel guilty for past discrimination by members of their race.

Or, that was the intent. That law has since been blocked.

In the wake of the newly adopted academic standards for Florida schools, Orlando Weekly spoke with Dr. Robert Cassanello, an associate professor of history at the University of Central Florida.

Cassanello, who also serves as president of the university’s full-time faculty union, has an educational background in Florida’s civil rights history, Jim Crow and labor. He is also a plaintiff in one of the first legal challenges to the “Stop WOKE Act.”

Robert Cassanello

Dr. Robert Cassanello, an associate professor of history at UCF, has concerns about new history standards in Florida schools that critics deride as “whitewashing” Black history.

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Orlando Weekly: What is your understanding of what these new standards do, or what purpose they will serve, within Florida’s public education system?

Robert Cassanello: These standards, I think, continue a trend in Florida that really kind of goes back almost 20 years, at least 15, to sort of strip interpretation out of history, and really try to whitewash history in a lot of ways. And when I say whitewash, I mean that literally. I took a look at the standards this morning, and you know, it really kind of shocks me how naked the attempt [is] to sort of revise African American history to one that is something I don’t think most scholars recognize. I think that the term that I’ve heard most often in the last few days with the standards, it’s “both sides-ism,” right?

To give you one example: When the standards examine racial violence, specifically the Ocoee massacre, there’s a phrasing in there that said something like, instruction on violence to African Americans and by African Americans. As if, well, you know, African Americans also committed violence to white folks presumably. And you know, it doesn’t really bear out in the standards where that might come in. But it’s there, if you want to explore that concept of both sides and say, well, there’s racial violence against African Americans, and then, you know, there’s racial violence against whites — which I think a teacher would be hard-pressed to find to be able to include in some kind of social studies lesson in middle or high schools.

OW: Right, I think one teacher was quoted in their critique of the changes as describing the new guidelines as presenting “only half the story and half the truth.” Do you think that’s a fair way to describe this?

Yeah, I think so. One of the other things that stood out to me is, they’re really trying to accommodate what they refer to as “white guilt.” That concept that Chris Rufo and DeSantis — you know, the architects of the law against critical race theory, known as HB7 — really tried to perpetuate this notion that whites can’t feel guilty for past inhumanity to other people. And we see this, I think, in the standards when there is discussion of the international slave trade, specifically [on page 8, SS.912.AA.1] — the Atlantic slave trade.

So in that section of the standards, what we’ll notice is that teachers are asked to discuss the origin of slavery in West Africa, slavery in Asia, slavery with the Barbary Pirates of North Africa, and slavery with the indigenous people of both North and South America, right? But nowhere in these criteria, in these bullet points, is there a discussion of slavery in British North America, or slavery with Europeans. Like what was their role in creating slavery and slave institutions? It’s completely absent in the standards, as if slavery was really a non-European thing in its totality. And I think this goes into trying to explain or at least justify the notion that whites have no reason to be guilty for slavery, because white folks had no role in slavery. It’s really kind of … I mean, it’s beyond laughable, you know, it’s really almost offensive, I think.

OW: You mentioned that this kind of change in instruction has been a trend over the past 15 to 20 years. So from a historical standpoint, have we in modern history seen this kind of whitewashing before in the state curriculum? And if so, where and when have we seen this?

The whitewashing of the history curriculum goes back decades. In the 1960s, there was a third group of scholars — historians, really — who came along and began to question these kinds of celebratory histories of the United States and sort of question why are we teaching about the founders as if they were the progenitors of, you know, the notions of liberty and equality for all, when they weren’t, right?

And so, this really kind of started a dialogue and a discussion that really would bear fruit in the 1980s — 20 years later, when states began to revise their history standards or social studies standards, and began to include the lives of African Americans, the lives of Asian Americans, the lives of people from Latin America. And it became a much more diverse and inclusive curriculum. And what we started hearing in response to that from conservative activists was this idea that, you know, the “real history” is no longer being taught — like Thomas Jefferson and James Madison and such were being removed [and replaced with] the likes of Frederick Douglass, Harriet Tubman, and things like this. That really started in the early 1990s.

And in Florida, in 2008, is when the state legislature really kind of adopted that philosophy to change the history standards in Florida. They began to introduce things like the genius of the founding fathers into the history standards, promotion of free market capitalism, free enterprise, and the creation of America.

I think HB7, when that comes along in 2022, that seizes upon that same movement, except it’s specifically directed at race. It has this kind of racialized intent, so that it muzzles professors so they can’t really speak about institutional, structural racism. You know, we see that in the standards that came out this week, because in these standards, the founders are referred to as the “architects of liberty and equality” [as if] they were working feverishly to end slavery in America. And you’re left with the notion that well, it was the 19th century. [There were] those people, those Americans in the 19th century that continued slavery when the founders really were working their best to eliminate slavery. And of course, that really isn’t true.

OW: So, what do you think is propelling the changes being made today, and within the last couple of years?

I think the changes are part of a conservative effort to manufacture a cultural war. And what I mean by this is, that there is a political benefit for people who are interested in sort of manufacturing the “other.” And then manufacturing people who are “disunited.” I think what the standards represent is a blueprint for conservative politicians and conservative activists to point to and say, “Look, this is what’s wrong with the way history is being taught, and here’s the way it should be taught.” And it’s being done in ways that enshrine it in legal pathways. Like, what happens if you don’t teach this stuff, if you’re a K through 12 teacher? You’re in violation. Presumably, you’re in violation of your job as a public school teacher. So I think these things really do serve that cultural war purpose.

OW: And how do these new standards adopted this week fit within the DeSantis administration’s broader education agenda?

These standards fit in DeSantis’ broader education agenda by infusing this fear of critical race theory, institutional racism and structural racism. You know, these are the pillars of DeSantis’ education policy in regards to the teaching of history and social studies. I think what [the] standards that were released this week document is really the stripping of African American history, of any kind of discussion about the consequences of racism.

OW: These new standards are tied to HB 7, the bill that you mentioned earlier from last year, more commonly known as the “Stop WOKE Act.” You’re a plaintiff in one of the first lawsuits to challenge that law, which has since been blocked. As a plaintiff in that lawsuit, and as an educator yourself, what kind of impact do you see these changes, these targeted attacks having on the educational workforce, or what have you observed already?

As a plaintiff in one of the HB 7 lawsuits, I really have a great deal of concern over the standards because the students I will get — most of the students that I will get — will come from an education system that presumably will be teaching these standards, and I think they will be ill-equipped to have the kind of foundation needed to really learn history effectively and learn history holistically.

So on that level, it really concerns me, because I may have to reteach a lot of students. I can’t tell you how many times a student will come into class and say, “Well, this is what I learned in high school.” And I would imagine that this will be much more pronounced after these standards are put in place.

The other concern I have is that of self-censorship, because what these standards do is set a tone. And again, the whitewashing isn’t as explicit as one might think, but it is certainly there, and I think what it does is it’s going to create a condition by which history teachers throughout the state are going to be questioned on what they can and cannot teach in regards to the history of racism in this country, and the role and responsibility of past actors to that history.

Just yesterday, as a matter of fact, a high-school history teacher contacted me and said, “What am I going to do with these standards?” This person was panicking. And at the moment … I just didn’t know what advice to give them at that point. But I would say to anyone who’s struggling with these standards to continue to teach what is accepted history, what is out there as historians tell them. I think the [new state] standards weren’t created by historians or with historians in mind. History teachers really need to feel that they’re not bound by those standards if they’re going to serve their students.

OW: Is there anything about the media coverage of these new standards so far that you think has been misconstrued? Or is there anything missing from it that you think is important?

Everything I’ve read so far, their characterizations seem to be what I read too in the standards. The only difference is there’s a lot more there to substantiate those characterizations than we’ve read in the stories.

OW: Right, yeah, it’s a 216-page document so there’s obviously a lot in there.

Right, and it’s kind of curious, because the section with the most revisions is the African American standards. And what’s sort of fascinating is the way that in parts of that they’ve kind of centered white history in African American history. It’s almost as if African Americans are sort of secondary in the section that’s supposed to be about the history of African Americans in this country.

One of the things that I’m really kind of curious about, I can’t figure out, is there’s a section there, a standard on violence, right? And so I know a lot of people picked up on the “violence to, violence by” African Americans. A lot of people picked it up. That’s great. That’s certainly troubling. But if you read further into that standard, there’s this [section]: ‘Discuss,’ it says, Lincolnville and St. Augustine, and this other town in Oklahoma. And why discuss those in terms of violence? I know Martin Luther King had called St. Augustine the most violent city in America in 1963 and ’64 when he was marching there, but Lincolnville? This was a black community in St. Augustine when Martin Luther King was there. So it doesn’t really explain, why is Lincolnville connected to the stories of violence? If I were a teacher, you know — not having a PhD, or being a historian — when I was in the classroom, I wouldn’t know what to do with this Lincolnville material. Like, what am I supposed to do with this? How am I supposed to speak about Lincolnville and violence? I don’t know. It’s not in the standards anywhere. And in fact, I even went online, because I was curious myself, like, what’s the violence in Lincolnville? And I did a Google search, and of course, nothing comes up [beyond information related to St. Augustine.]

OW: Is there anything else about these new standards, and what they mean for the state of public education, that I haven’t asked about that you would like to share?

I hope the public really does pore over this and takes an interest in what the state says history teachers should be teaching in the classroom. Because, again, this goes back at least to 2008 when lawmakers in Tallahassee demanded that history teachers do not teach opinion, do not teach interpretation and only teach facts, right? And I think lawmakers putting themselves into the classroom in this way is really harming the teaching of history as a discipline in K through 12.

And I do hope that this wakes people up and makes them say, hey, perhaps lawmakers aren’t the best person to decide what history teachers should be teaching. Perhaps it should be the experts. There’s history and social studies teaching organizations that devote time and effort into all this, have conferences, produce resources and guidelines. It doesn’t look like any of that stuff was consulted on these standards. And I think it’s time that we take this to the lawmakers and expect more out of them and what they’ve been doing with history standards.

Subscribe to Orlando Weekly newsletters.

Follow us: Apple News | Google News | NewsBreak | Reddit | Instagram | Facebook | Twitter | or sign up for our RSS Feed