As the peak of the Atlantic hurricane season is upon us, a group of elite pilots, scientists and meteorologists are gearing up for some of the most wild rides of their life.

As tropical systems form in the Atlantic basin, the National Hurricane Center keeps a watchful eye on where these systems will track. Occasionally, some storms may pose a threat to land or large population areas and more data may be required to provide an accurate forecast for these locations.

That’s when the National Hurricane Center may request for the Hurricane Hunters to investigate a system.

(AP Photo/Gemunu Amarasinghe)

In the United States, we have two teams of Hurricane Hunters. The first is the United States Air Force Reserve 53rd Weather Reconnaissance Squadron, which is the world’s only operational military weather unit.

This squadron relies on a fleet of 10 Lockheed WC-130J aircraft, which can fly directly into a center of a tropical system. These planes typically fly missions between 500 feet and 10,000 feet off the ground, depending on the strength of the storm.

The other team of Hurricane Hunters are a civilian team that comprise the NOAA Hurricane Hunters. This team, composed of scientists and meteorologists, performs surveillance and research flights into systems.

While NOAA maintains a larger fleet of planes than the U.S. Air Force, NOAA only uses three planes for hurricane missions. That includes two Lockheed WP-3D Orion aircraft and one high altitude G-IV Gulfstream jet.

The NOAA WP-3D Orion aircraft – like the Air Force’s WC-130J planes – are used to fly directly into the center of a storm. This provides information on where the center is located, as well as data regarding the strength of the storm’s eyewall.

The plane also is equipped with a tail Doppler radar, which can fly radar missions to provide a better look in at the rain bands in areas where no radar coverage exists. This is especially helpful in the open waters of the Atlantic.

(NOAA)

The G-IV jet does not fly directly into a storm but around and above the system at heights of 30,000 to 45,000 feet. This plane will sample the environment around the storm, which helps with long-term intensity model forecasts. The G-IV jet is also equipped with a tail Doppler radar and can also fly Doppler radar missions in and around a storm.

NOAA also plans on taking ownership of a new Gulfstream 550 jet by the spring of 2025. This jet will fly higher and longer than its current G-IV jet. This will also expand the capabilities of NOAA to provide more missions as longer and more active hurricane seasons continue to take shape.

How do the Hurricane Hunters gather data?

So what’s the point of flying into, or around, these tropical systems? For NOAA, it’s simple – Data.

The more data they have, the more likely the forecasts for these tropical systems will be accurate. And an accurate forecast, NOAA says, can provide better lead time for those in the path of a landfalling storm.

This can give cities, towns and individuals more time to prepare for a storm’s impact and may also allow for a larger time for those needing to evacuate to do so.

Data can be collected several ways. All the planes the Air Force and NOAA fly are outfitted with several sensors on the outside of the fuselage. These sensors can provide data like temperature, wind speed, pressure and rain intensity. But what about all the data that can be obtained from underneath the plane’s flight pattern?

(NOAA)

That’s where a little instrument called a dropsonde comes in.

Dropsondes are small instruments that are dropped out of a plane attached to a small parachute. The instrument floats down to the surface of the water, recording various weather data parameters, like temperature, dew point, wind speed and pressure.

The sensor is also outfitted with a GPS locator, which can be tracked to provide wind direction at various altitudes of the atmosphere.

Because these dropsondes are dropped from the plane and land on the surface of the ground, that’s why Hurricane Hunters will never fly over land. To limit the risk of harming anyone, these flights are strictly done over the open waters of the Atlantic so the dropsondes can harmlessly land in the open water.

So how do they fly into these storms?

Hurricane hunter flights are methodically planned, with a team of navigators and meteorologists working together to make sure they achieve maximum data while also staying safe during their flight.

However, over the years, the Hurricane Hunters have devised several specific patterns that have become the norm to fly.

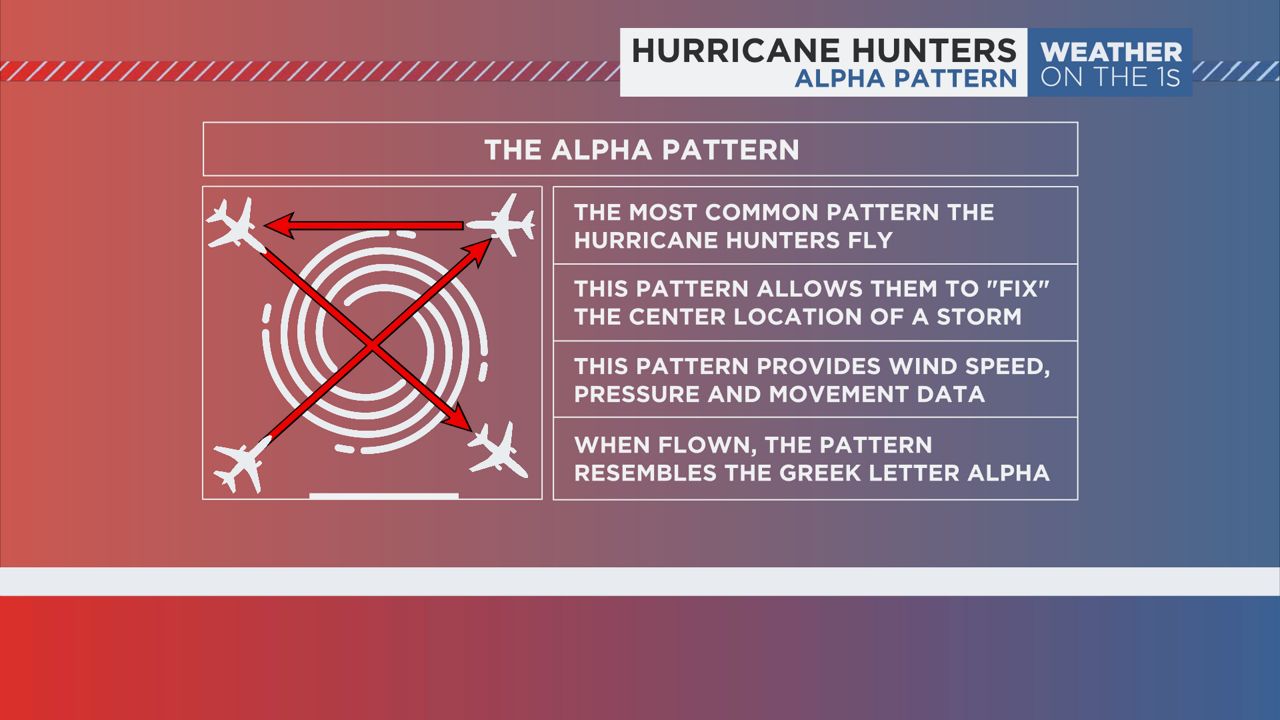

The most common pattern is known as the “X” pattern or the “Alpha” pattern.

This pattern is flown by the Air Force’s C-130J or NOAA’s P-3 Orion aircraft. In this pattern, the plane will fly to one corner of the storm before turning to fly directly into its center.

Once in the center, the plane will “fix” the exact location where the wind shifts, showing the center of circulation for the storm. Once it’s fixed the center, it will fly out the other side to the opposite corner of the storm.

From there, the plane will turn flying to the third corner before it turns back in toward the center once again. This will allow for another “fix” of the storm, providing a timeline of how the storm is moving.

This pattern provides the best opportunity to provide location, wind speed and pressure information on the developing tropical system.

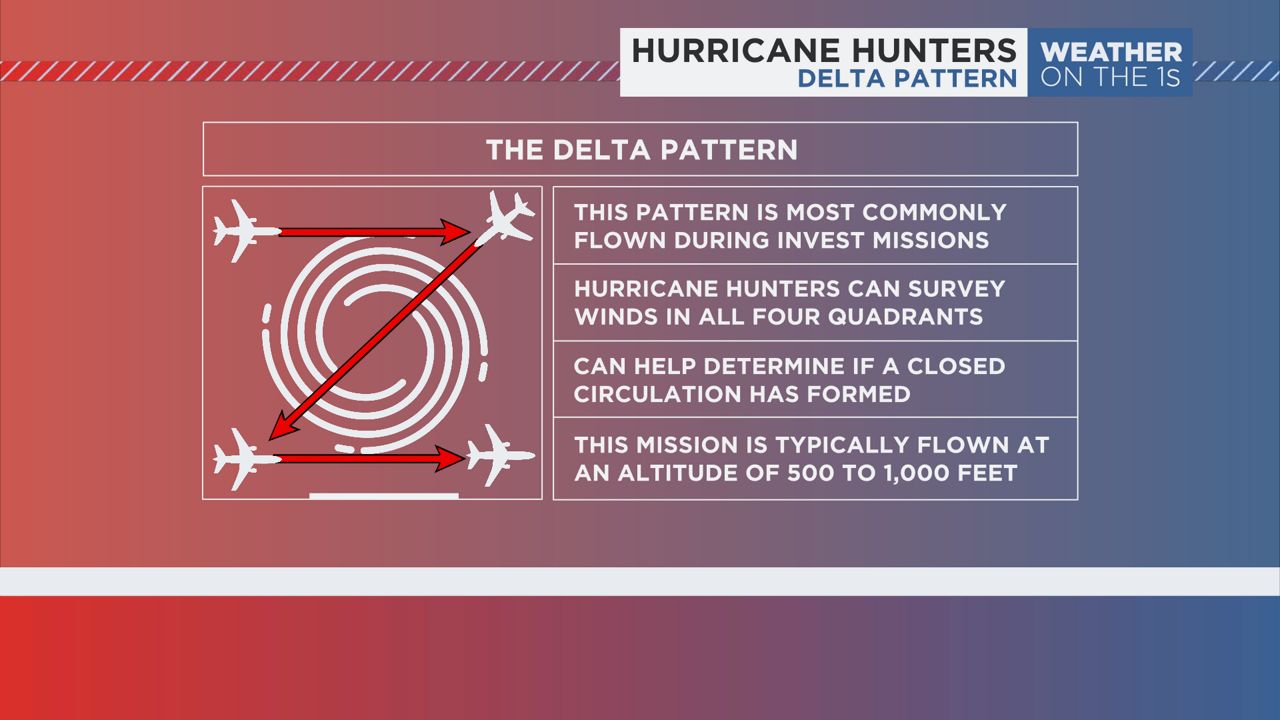

Another pattern used frequently by these planes flying into the center of the storm is the “Delta” pattern. This is most commonly flown when a storm is in its infancy – typically as an invest.

This pattern allows the planes to fly through all four quadrants of the storm, allowing them to search for a closed center of circulation. A closed center of circulation is a requirement before any system can be deemed tropical.

These missions are flown at a very low altitude, typically between 500 and 1,000 feet. This provides as close to a surface observation as possible.

Several hurricane hunter pilots have said these missions can be more intense than major hurricanes, as invests tend to be messy and very sporadic with how the thunderstorms develop. This can cause a very rough ride.

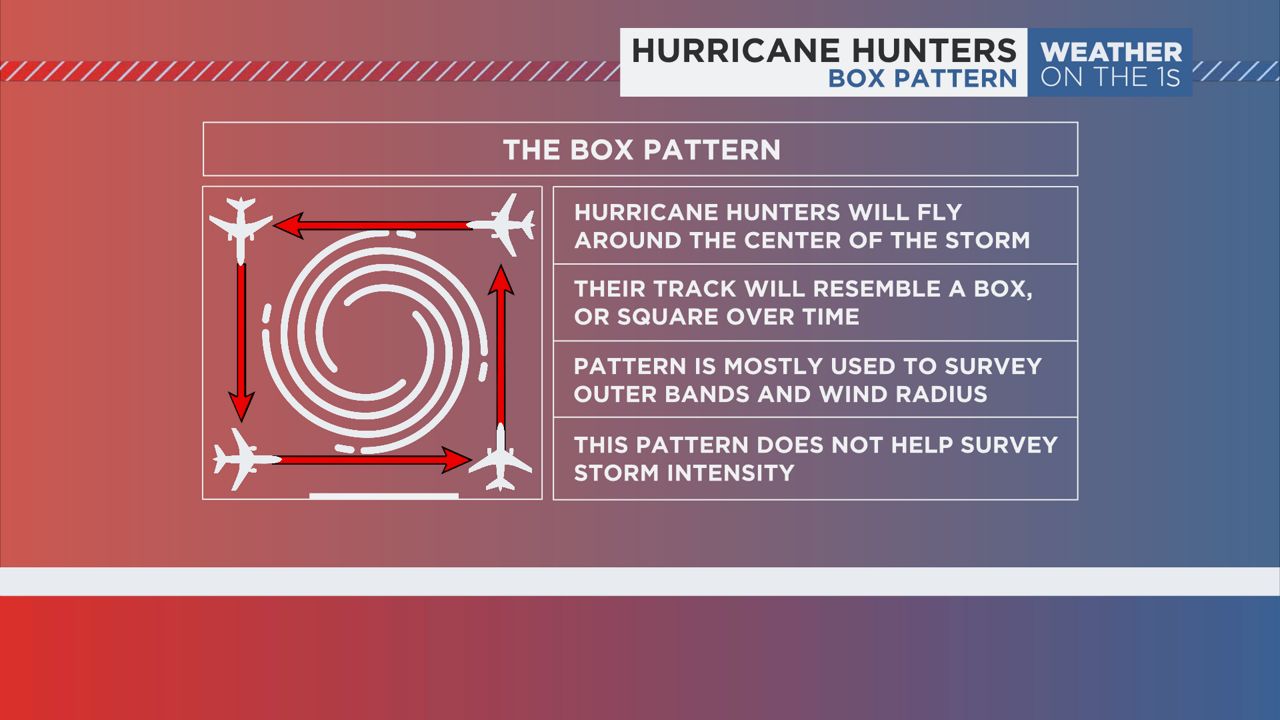

Finally, the “Box” pattern is the third most common pattern flown by the Hurricane Hunters. This is most commonly used by NOAA’s high altitude jet, which flies above and around the periphery of the storm.

This can allow the pilots and scientists onboard to survey the storms outer most rain bands, either with dropsondes or the tail Doppler radar.

This pattern helps provide a better picture of the structure of the storm, as well as the environment the storm may be moving toward over the coming days. This pattern does not provide any information regarding storm intensity.

There are several other various patterns that the hurricane hunters fly, including the Star, Lawnmower or the Square Spiral patterns – each with their own pros and cons.

As the peak of season continues to get underway, know that these elite teams of meteorologists, pilots and scientists will continue to provide crucial data to keep us all safe. And that data comes only by flying into these hurricanes.

Our team of meteorologists dives deep into the science of weather and breaks down timely weather data and information. To view more weather and climate stories, check out our weather blogs section.